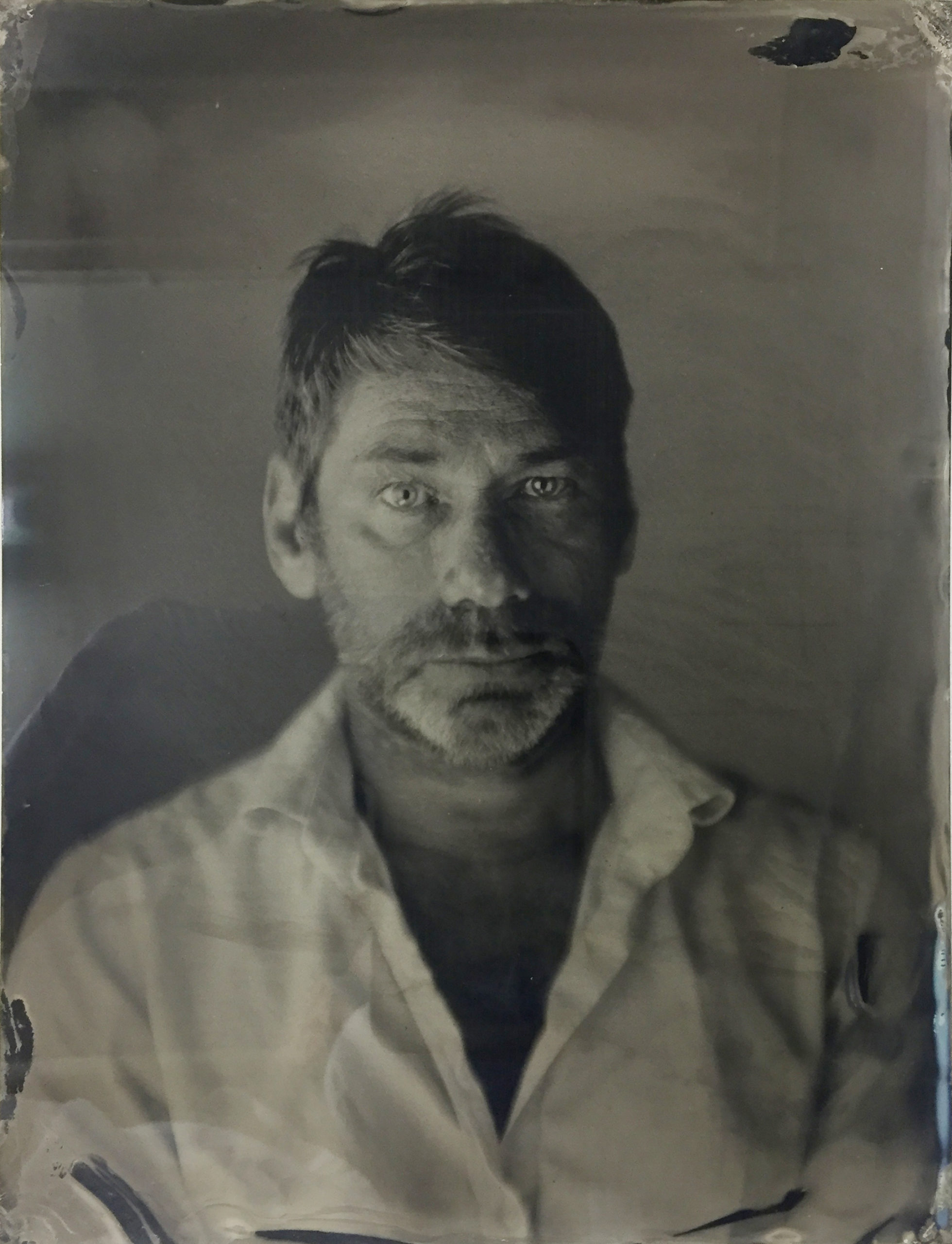

Mat Collishaw (*1966, Nottingham) is one of the most significant and compelling artists in contemporary British art. With an early foundation at Goldsmiths College, Collishaw formed part of the legendary movement of Young British Artists. He was one of 16 young artists who participated in the seminal Freeze exhibition organised by Damien Hirst in 1988 as well as the provocative Sensation show of 1997.

Throughout his 30-year career, Collishaw has contemplated the nature of the human subconscious and explored ways to influence it through various media. Through optical illusions, paintings, projections and moving sculptures, the artist creates works and scenarios that directly and unconsciously engage their viewers. The works encourage us to think about fundamental questions of psychology, history, sociology and science. Behind the richness and visual appeal of each work there is a deep exploration of how we perceive and are influenced by the world today through images, and modern technology.